The career of Lorraine Carolan – Part 2

By Ann Constantino,

This is part 2 of 3 looking back at the 50-year career of Lorraine Carolan, longtime community healthcare activist, Licensed Midwife and Physician’s Assistant.

Redwoods Rural Health Center opened in 1976. The center was founded by a group of new settlers to the area, spearheaded by Lorraine and Kate Lanigan who had been working together as local homebirth midwives. From its inception, the clinic was a place where the patient was encouraged to be active, to be an integral part of her care, turning upside down the doctor-centered model many in the area had grown up with and intended to leave behind. “We knew the care (offered by the clinic) had to be accessible and relevant,” says Lorraine.

A holistic community

In a community beginning to define itself as a “back-to-the-land” movement in which growing and raising one’s own food, utilizing alternative energy systems, and building homes that had a gentler impact on the earth, RRHC was a natural fit; and Lorraine’s “midwifery model of care” found a groove. During a time of hopeful excitement accompanied by a willingness to learn the skills and endure the hardships of living close to the land, alternative healthcare and what was at the time called “natural childbirth” was perfectly suited to the young community.

“Irv Tessler, MD, was our first doctor as we began our ‘clinic’. Irv was a psychiatrist and that training definitely fit into our model of holistic (whole person) health care. His skills, humor and honesty were so supportive of our early efforts,” recalls Lorraine.

By this time, the active organizing group was enlarging. And the community interest was high. Jimmy Durschlag was RRHC’s first Director and he was very effective at writing grants and looking for funding. “We also relied on volunteer labor and bake sales and boogies for money. We never charged money for births….thinking it ‘muddied’ the service nature of our work (we were very young!). This was early, prior to marijuana being the financial driving force here. Still, the community rallied and the support was there. It was during this time that the actual clinic opened at the space ‘next to the laundromat’ in Redway. As well, we now had a doctor trained in primary care, who was interested in our mission.”

Prior to coming to Southern Humboldt in about 1978, Bill Hunter, MD had backed midwives helping at home deliveries in the Sacramento area. California was experiencing a resurgence of midwifery in small pockets all over the state.

Of Dr. Bill, as he was affectionately known during his long tenure in Southern Humboldt, Lorraine says, “In his own words, Bill once said ‘The clinic here [RRHC] fit in with a lot of my ideals. It was community owned and operated. It was created by the consumers, who were consciously trying to achieve a blend of approaches and therapies.’ Regarding his work with midwives, he became convinced that by offering clear communication and medical backup for the womens’ choices, there would inevitably be better outcomes.”

In fact, the outcomes were very good. “Even with a somewhat diverse population, our C-section rate was under 13%. [The average rate of C-section deliveries was almost 23% in the 1980s across the US.] There were very few preterm deliveries. We had predominantly healthy moms and babies,” reports Lorraine.

Golden age of community clinics

Against the backdrop of what Lorraine calls the “golden age of community clinics”, the group of early midwives “called ourselves the ‘daughters of time’. We were on a new frontier: in the north country of California, the edge of the world. We were creating our own interpretation of healthcare, at first for women, but then it became a clear model for healthcare delivery for everyone.”

Women and families wanted to experience and participate in pregnancy and childbirth as a healthy part of normal life rather than as a medical event necessitating doctors calling the shots as the mother-to-be obediently complied.

Lorraine’s role as advocate for what she now calls “authentic birth” had already taken her into hundreds of homes to assist in the delivery and post-partum care of babies being born as nature intended. Now under the umbrella of the newly formed health clinic, holistic pregnancy care began to seem less like an idealistic pipedream and more like the local norm.

Bob Mathes, MD. joined the clinic in the early 1980’s. Lorraine remembers: “We were growing bigger. Both Bill and Bob were patient and excellent teachers. They had each questioned their own medical training . The prenatal group (midwives, nutritionists, birth educators and coaches) met weekly and discussed each woman’s case. The medical staff also met weekly. The entire staff met as well. Collective operations demand a LOT of meetings, attempts at different avenues of communication. It was sometimes exhausting and frustrating…often exhilarating. Mostly successful on many levels. We were so human and as flawed and creative as that implies. I, and I believe most of us, were committed to the work with an almost revolutionary fervor. But it was the work of privilege. By this I mean, we had time and were fueled by ideas and ideals…and the youthful energy to put them into actions. The early days of the Clinic were the embodiment of americana hope.”

“We were still in a geographic and ideologic bubble in Southern Humboldt, Northern Mendocino and Western Trinity counties. Our influence and service area was over a thousand square miles. In the grants first written, Redwoods Rural’s Prenatal Program was the flagship model. We incorporated community-based care driven by the needs and engagement of that community. Outreach workers were an integral part of our services. Despite this, finding obstetrical backup for our prenatal clients was not easy.

“We are all imbued from birth with cultural suppositions, even myths. Growing up as I did our family doctor was revered as much or more so than the parish priests. He did home visits and they were treated as visitations from a saint. That kind of conditioning is very hard to shake.”

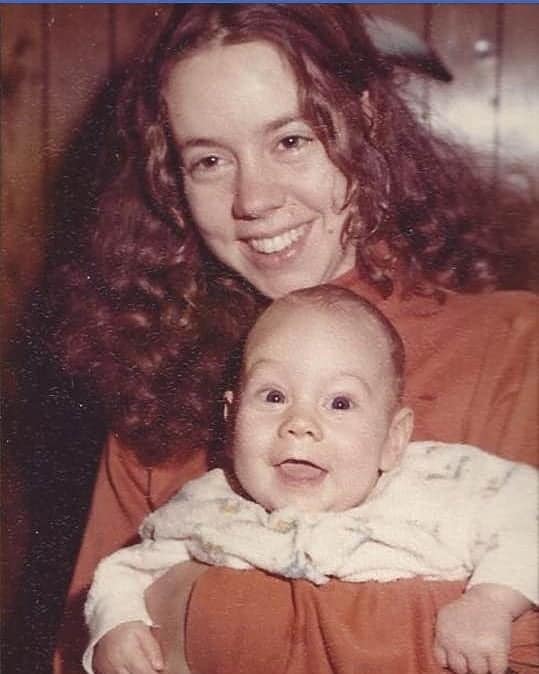

Advocate for a young mother

Lorraine tells the story of a young mother, pregnant for the second time, who sought a natural birth for her second child after having had a Cesarian section for the birth of her first. She felt that she had not been listened to or encouraged during her first pregnancy and delivery. She was a young teenager and felt railroaded into a surgical delivery because the “baby was too big for her pelvis”…a common reason for not encouraging or allowing a vaginal delivery. Vaginal birth after Cesarian (VBAC) was almost unheard of at the time, the medical assertion that whatever circumstances led to the C-section in the first place held true for all successive pregnancies, like an unimpeachable rule. But this young woman was determined, even as she went through her pre-natal care and was turned away by many Humboldt obstetricians who would not take on what was assumed to be a big risk by allowing her to deliver vaginally.

We finally found an OB/GYN in the Eureka area who agreed that the birth she hoped for was medically safe and plans were made to deliver under his care, with Lorraine assisting. Yet, when she began to go into labor and made that long trek to the north part of the county, that particular doc was not available. The young woman was not dissuaded. Lorraine, who was in complete support of the vaginal birth, began calling every medical facility on the Northcoast and finally found a Doc in Fort Bragg who agreed to the vaginal birth. However, by this time, labor was progressing rapidly and Lorraine realized there was not enough time to make the long windy drive to Fort Bragg. She and the laboring woman stopped at RRHC where a makeshift delivery room was fashioned. Local RN Rena Kay was called to assist, and a beautiful healthy baby (a full three pounds heavier than her first, by the way) was delivered vaginally in the back room of a homegrown rural community clinic founded on the midwifery model of care.

The road to legalization

Midwives had been jailed and harassed, sued, and treated as criminals on the road to this law.

Arcata’s Northcountry Clinic For Women and Children, founded in the mid-1970s on many of the principles shared by RRHC, participated in a statewide program which developed the specialty designation of “Women’s Healthcare Specialist”. Lorraine did some of her formal training through this program which later dovetailed into the early Physician’s Assistant (PA) training program. Medics returning from the Viet Nam war were highly trained and deeply experienced and so the PA program was created to both validate and take advantage of that background by giving a mid-level provider’s medical license without necessitating a full university degree.

Local midwife Kate Lanigan had obtained her Physician’s Assistant license and the clinic encouraged Lorraine to do the same. Kate was able to follow women through if they needed hospital transport; and for Lorraine, that was an appeal. In 1982 she passed the California board exams to get her PA license.

Yet, non-nurse midwifery was still not legal in California. Legally, homebirth was in a grey area subject to interpretation by local and state authorities. During this time, Lorraine was participating in meetings of the California Association of Midwives, a group working to make non-nurse midwifery (aka “lay” midwives) and through that, homebirth, legal in California. “I helped write the language, as part of a team effort, of the licensing bill, so I felt a strong affinity for licensure and the early emphasis on community peer participation and peer review. There was an emphasis on core skills and knowledge, basic and universal.”

The bill did not become law in California until 1993. It was the culmination of a great deal of work and sacrifice. Midwives had been jailed and harassed, sued, and treated as criminals on the road to this law.

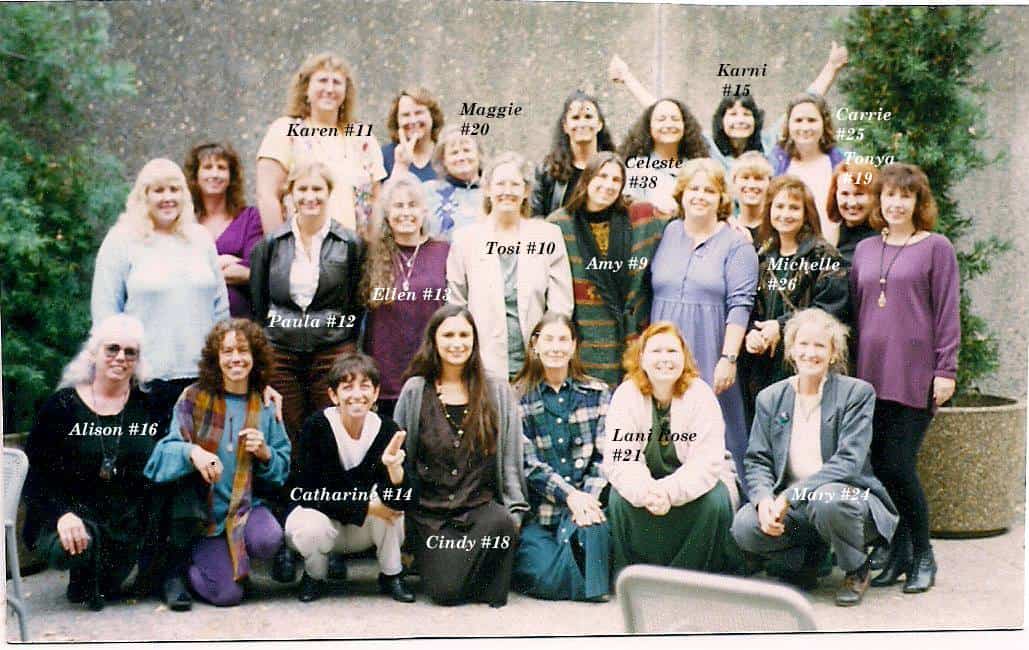

Training future birth workers

At the same time, Lorraine and Kate were training and mentoring numerous women to work as birth workers and future midwives as a SoHum baby boom was in full swing. “At first we worked as a collective, sharing what we each brought. That communication approach didn’t really change but evolved into the apprenticeship model. My teaching approach was a classical apprentice model of observation and participation. Everyone has a different way of learning. Apprenticeship enables the method of learning to be more personal. Working with individuals or small groups worked best for me over the years.”

“A lot of this, my personal evolution as a healthcare provider, I felt was part of what helped inform my philosophy but also the culture of RRHC at that time. And it was the gradual recognition that there was tangible, in-the-body proof, that the medical model was skewed, not based on individual health needs and a sense of personal engagement and authority; and in fact the concept of women’s (or anyone’s) empowerment was an antithesis to the dominant medical model.”

Lorraine tells the story: “I recall several years into the clinic, Bill Hunter came into a room to get me. He had been doing a well-child examination. The little girl was getting some immunization shots, and was quite resistant. She began singing at the top of her lungs….resonating throughout the clinic halls: “My body’s nobody’s body, but mine. You run your own body, let me run mine.” It seemed proof of success of one of the prime values we had begun with. A new generation voicing need for some autonomy.

A shift in healthcare

The depleted and shrinking coffers of public funding were not being replenished.

Sadly, and not without great irony on the heels of legalized homebirth, the ugly spectre of managed care began to dominate conversations among healthcare administrators everywhere in the US in the mid-1990s. A system designed to cut sky-rocketing medical costs, managed care ushered in micro-management of providers’ time spent with patients, limited services, and otherwise made everything that RRHC had originally stood for no longer cost-effective, all while handing over more and more medical decision-making to for-profit insurance companies.

The depleted and shrinking coffers of public funding were not being replenished in a time when Reaganomics was overseeing an upward flow of wealth, leaving many Americans hopelessly underserved. Locally, RRHC and the Garberville Clinic under the umbrella of (what we now call) Jerold Phelps Community Hospital, reliant in large part on public funding, were in a sense pitted against each other in a competition for that diminished funding. Boards of both organizations agonized over the idea of merging. What seemed on the surface like a reasonable consolidation of duplicated services turned into a deep ideological rift that ultimately saw Hunter and other providers leave RRHC, while Lorraine and popular Doc Ron Hood, and a few other providers and staff, stayed at Redwoods Rural, each entity hopeful of retaining its individual strengths. The toll of the deep divide in the community was great: a loss was felt by both institutions and irreparable damage was done to professional and personal relationships despite hours and hours of community meetings to hash out various merged scenarios. As it turned out, a merger would not have even been legally possible given the funding regulations of each entity. Lorraine says of the time, “It was unbelievably difficult and many of us at RRHC worked for months with little or no recompense.”

Birthing center closes down

What came next, in 1997, and signaling another devastating layer of disillusionment to community-centered healthcare, was the closure of the birthing center at Jerold Phelps Hospital. Birthing services have never been profitable, but what had been a community’s tremendous accomplishment of rising above the profit-centered medical model to deliver outstanding levels of care to birthing families in the pocket of self-determination that Humboldt had evolved into, suddenly found itself without a crucial operational facility.

Lorraine recalls: “We argued, cajoled, begged and cried to keep hospital back-up and the birthing room open. I kept saying when women leave the area to have their babies, the sense of place is eroded. Families will leave for other medical care. It will begin an exodus that will be difficult to counter.”

With medical back-up an hour or more away, the prospect of home birth was less desirable for young families. For families not inclined toward homebirth, babies were no longer being born in the SoHum community, a fact which on its own changed the social landscape of the area, just as the area was about to experience the financial impact of medical marijuana, legalized in 1996.

As a lack of funding characterized a debasement of local healthcare and especially birthing services, Southern Humboldt could hardly imagine the “greenrush” about to occur that would cause a huge shift in the local economy, sparked by a new legal interpretation of the medical properties of a humble weed.

Next time

Lorraine’s role in medical marijuana, and the beginnings of renewed interest in authentic birth as the next generation seeks the empowerment their mothers and sometimes even grandmothers experienced during the SoHum homebirth revolution.

Ann Constantino, submitted on behalf of the SoHum Health’s Outreach department.

Related: Healthcare, Pregnancy, Women's Health