The career of Lorraine Carolan – Part 1

By Ann Constantino,

This is part one of a series looking at the career of Lorraine Carolan, arguably the most influential healthcare provider in our community in modern times. She has served for over 50 years as a midwife, women’s health specialist, physician’s assistant, health educator, and medical marijuana advocate. The reach of her unwavering dedication to holistic care can be felt not just locally, but throughout the state, as she was instrumental in legalizing non-nurse midwifery in California.

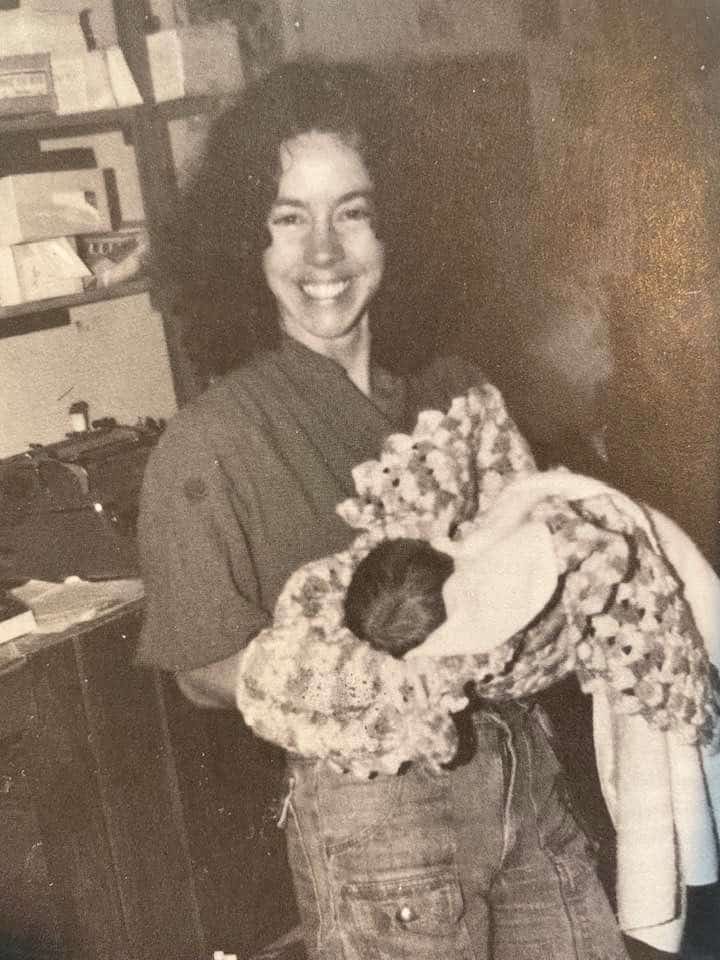

The first of thousands of births

1966. Two young women, close friends and college students, rode in a taxi paid for by an unknown family from where they lived in New York City to a hospital in Newark. One of the young women was going into labor. Her friend, who worked at a factory in Newark, had been taken under the wing of her older female co-workers when she asked them, “What do people do when they have a baby they want to give up for adoption?”

She was given the name of a Newark doctor and told, “He will help you.” And so arrangements were made. At the hospital, the friend stayed nearby until the laboring woman was taken to the delivery room. After the baby was born, the friend was given the tiny infant and she carried him down the hall to hand over to the arranged adoptive parents, an affluent white family who had paid for all the medical expenses of their new child.

This turned out to be the first of thousands of births that Lorraine Carolan would support, whether through hands-on participation as a midwife, or as a longtime mentor to many midwives in our community, or through her many years of providing pre-natal care and health education.

“Every child deserves to be born wanted and able to be cared for.”

“The taxi home cost 20 bucks,” says Lorraine, noting that expense was not covered. “We cried a lot.”

The socio-economic conditions for a young Catholic woman in the sixties presented no other options. The system would not support much less condone an out-of-wedlock child belonging to a college student. Lorraine realized in that time that “every child deserves to be born wanted and able to be cared for.”

Sadly, despite a renaissance of authentic births that took place on the north coast through the 1980’s and 1990’s enabling hundreds of local families to experience birth as a joyful social event rather than a medical intervention, Lorraine fears we may be right back where we started, in the relative dark ages of childbirth that her friend experienced in 1966.

Raised in a working-class family in northern New Jersey, Lorraine was the third of five children and was not particularly drawn to the acceptable careers for young women of her time, such as teaching school or becoming a nurse. An avid reader, she studied journalism and theatre at Rutgers and The New School. She worked in bookstores and libraries and became politically active. She hitch-hiked across the US several times and traveled to Europe, once being deported from England for wearing a nuclear disarmament button.

Experience with home birth

Eventually, she found her way to Whitethorn in 1968, and became one of the original new settlers on the north coast. “There was a library in Whitethorn and I read lots of books about lots of things. My friend was pregnant so I started to research pregnancy and birth. I ordered a lot of books, there weren’t many, on breathing techniques because I was going to accompany my friend to the hospital when she had her baby.”

Friends wanted to have their babies at home, a logical outgrowth of the back-to-the-land movement.

Soon, other friends decided they wanted to have their babies at home, a logical outgrowth of the back-to-the-land movement at the time that rejected many of society’s norms. They asked Lorraine to attend and help with their births. “I was completely ignorant and said as much, but if you’re going to do it, I will be there.”

In 1971 Lorraine’s first child, son Devlin, was born. “There was no one in my immediate world who had any experience with home birth. No one had even had a baby.” When she started to go into labor at home, she recalls, “There were 5 or 6 people around and one pair of sterile gloves that my closest friend Barbara Sher put on as soon as my water broke. My son’s father and several other people were nervously standing around outside smoking cigarettes and it started to rain. Everyone was becoming afraid that it was taking too long so it was decided to take me to the hospital in Garberville.” Loaded unceremoniously into the back of a van, Lorraine arrived at the Garberville hospital where her panicked friends told the crew in the ER that she had been “pushing for hours”.

This information steered the docs toward a Cesarian section. But Lorraine had been taking prenatal classes with public health nurse at the time, Sally Mixson. Sally had advised Lorraine to ask for a quiet room where she could just breathe. “I went into a room with an oxygen tank and just started to open up to something bigger than me.” She was ultimately able to deliver vaginally, recalling that (Dr.) “Jerry Phelps held me through the entire thing.”

“That experience, even though they treated me fairly well, made me know that there’s a different way to approach birth,” says Lorraine.

Not long after, Lorraine heard of and began taking classes in the Eureka area with Bill Fisher, an EMT who was doing home births. There she met the late Kate Lanigan (longtime Physician’s Assistant and midwife at Redwoods Rural Health Center) and together they started attending home births, along with Gena Pennington, MD.

“Kate and I were both living in Southern Humboldt and began talking about the need for trained women to assist laboring and delivering mothers in our area….especially those who chose to deliver their babies at home.” Soon Lorraine and Kate were helping families together.

“It was in 1973 or 74 that we began meeting regularly with several people who clearly felt a need for a different kind of healthcare delivery, accessible to everyone.” It was decided to rent a space in Redway, not far from the very popular Mamie’s Diner, a social hub for newcomers and old-timers alike. The group wanted to attract attention to their budding alternative healthcare venue and thinking of the new settlers in the hills, realized basic conveniences would likely draw them in.

“We figured that people needed a bathroom and a telephone. So we got together those two services and lots of health educational information. The Open Door Mobile Medical Unit from Arcata began stopping there and we did prenatal exams on local women with Gena. And of course, other medical services began being offered. One day a guy comes in to use the bathroom and telephone and because he heard we were a medical place. We talked and he said, ‘Actually, I am a doctor, looks like you might need one.'”

That was the start of a relationship with Dr. Irv Tessler, who is now a long time local psychiatrist. “We all thought it so appropriate that given the nature of our care, our first real medical doctor was a psychiatrist” says Lorraine. Later, Dr. Bill Hunter became Redwoods Rural’s Medical Director. In the right place at the right time, Hunter was a Doc with the vision required to support the home birth movement as a member of the medical establishment. “We needed a bridge and Bill was it,” says Lorraine.

The midwifery model of care

By the time Redwoods Rural Health Center officially opened in 1976, Lorraine had become integral to the leadership of a collective of activist healthcare workers. The clinic was founded on the principles of the “midwifery model of care”, a radically holistic and patient-centered approach based on listening to the patient and providing space and education so that the patient becomes an active participant in decision-making. Ahead of its time in offering what is known today as “integrative medicine”, taking into account a person’s socio-economic background, personal family history, and all aspects of a person’s body, mind, and spirit, Redwoods Rural continued to provide holistic pre-natal care in a community that was very ready for it.

“This area became an oasis of natural childbirth.”

Meanwhile, the California Association of Midwives was pushing for the legalization of midwives attending home births without conventional medical intervention. Lorraine was an active participant in conversations that developed into legislation making it possible for families to bring their babies into the world in a home setting. Up to that point, only certified Nurse-midwives were legally permitted to provide support in hospital deliveries, and many of the home births taking place throughout our community were done quasi-legally.

“This area became an oasis of natural childbirth. Even though we didn’t have hundreds or thousands of births behind us, the medical establishment had to accept us, and we had a relationship with them. It had an economic effect as well. The public demand and the economic impact helped pass legislation that legalized non-nurse midwifery. Community-based midwifery and out-of-hospital birth greatly affected all of the obstetrical services on the North Coast. Midwives (although primarily Certified Nurse Midwives) eventually became an important part of almost every Ob-Gyn and Perinatal Service in the county.”

The “outlaw” aspect of providing home births suited Lorraine’s activist nature; and she and Kate Lanigan, along with many mentees, and local women who were drawn to birth work, facilitated the delivery of hundreds of babies at home. Several of the midwives became licensed, had hospital privileges, and were at the side of MDs doing more conventional or medically necessary hospital births, often receiving on-the-job training.

“Teaching went both ways: the medical doctors learned a lot from the midwives.”

“Dr. Jerry Phelps was a phenomenal, compassionate physician and a great teacher. He taught me to deliver breeches and twins. I remember early on when we had a woman with a retained placenta. Jerry Phelps and I had worked with this woman and her baby was delivered. Jerry said to me, ‘we have to go in and you have to do it, your hands are smaller than mine.’ It was an act of faith for a conservatively trained medical man. Yet, I remembered him holding me when I delivered my son. Once again, he had my back as I went in and worked that placenta out. It was validation and true training from an unexpected source. For all the negative things that can be said about some white male doctors, he was a good teacher and one of those bridges home birth demanded that we have and I will always value him for that. Yet the teaching went both ways: the medical doctors learned a lot from the midwives.”

Next time: The advent of managed care and its effect on prenatal care and home birth, the closure of birth services in the local hospital, and the legalization of medical marijuana.

Ann Constantino, submitted on behalf of the SoHum Health’s Outreach department.

Related: Healthcare, Pregnancy, Women's Health