Fitting Into Your Genes, Part II

By Ann Constantino,

Published in the Humboldt Independent on July 28, 2020

Read Fitting Into Your Genes, Part I

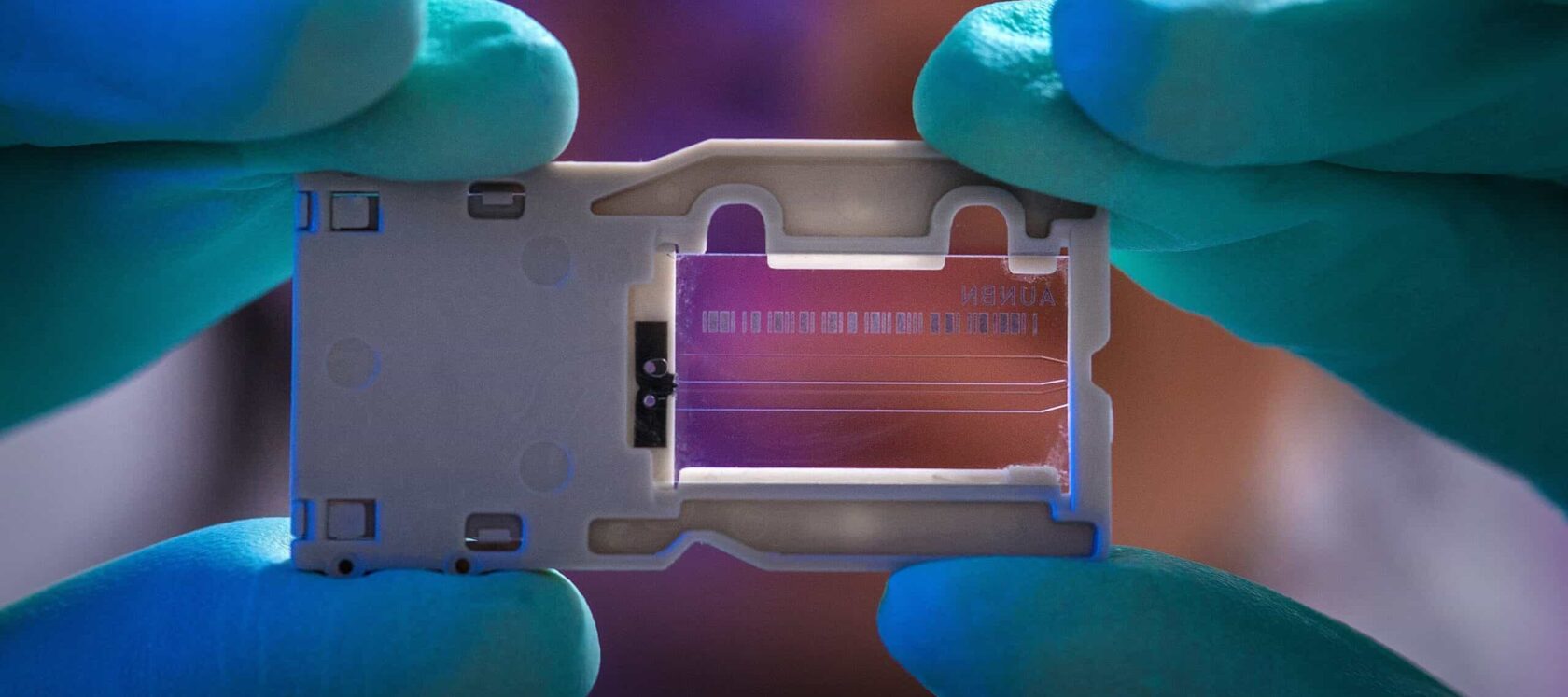

DNA testing

Millions of Americans have flocked to have their DNA tested over the past decade or so to discover their ethnic and cultural origins. The strong desire for this knowledge is likely a by-product of a melting pot society in which many of those origins have become forgotten, obscured, or lost over time, leaving us feeling undefined, out of place, or otherwise somehow lacking identity.

The environments of our once distinct and separate populations gradually conferred epigenetic changes on their occupants. For example, the high animal-fat diet typical of arctic populations did not damage the heart, European cow herders became able to digest lactose into adulthood, and Polynesian sailors developed a reduced need for vitamin C enabling them to fend off scurvy on long voyages. Had we remained this separate and distinct, Ancestry.com would never have existed as our family trees would contain no mystery.

The consumer-based DNA companies can predict the future of your health and your susceptibility to certain diseases.

It is now possible to obtain our genetic information relatively inexpensively. The consumer-based companies that offer the service can also provide results based on the same cheek swab or tube of saliva that they say can predict the future of your health, your susceptibility to certain diseases, even what foods you should be eating to maximize your health. Answering the “who am I” question may in theory also bring information relevant to health issues and diet choices.

Now having spread out all over the globe, once distinct populations have blended up more thoroughly than your morning smoothie and so have their genetic predispositions for health issues. Family trees include branches that carry a wide variety of potential influences on our health and wellbeing, and DNA testing companies are quite willing to cherry-pick from established data in order to provide you with information they imply can lead to better health outcomes.

While the consumer-based testing companies, as well as more sophisticated and vastly more expensive labs producing more complete sequencing info, promise all kinds of life-changing data that will make important choices clearer for their customers through the health-based reports supplemental to the heritage info, it turns out that even the more detailed genetic sequencing costing thousands of dollars actually leaves most questions unanswered.

The study of genes

Given that there are 3 billion base pairs of DNA (the instructional building blocks for the human organism) in our roughly 25,000 genes, science is a long way from understanding what all of the variables might mean in any one human specimen. When it comes to food and diet, it’s not just blended DNA that makes navigation difficult. Modern agriculture has changed the quality and variety of foods to a degree that makes comparisons to the past impossible. Studies have shown that identical twins do not necessarily benefit from the same dietary recommendations. Concerning other health issues, stress and environmental degradation have changed our susceptibility to disease, muddying the waters of purely genetic understanding even more.

There is simply not enough data to reliably predict what variants or unstudied combinations of variants in your DNA will do.

However, there are quite a few well-studied genes and their variants that do deliver proven information about your health. A discussion with your medical provider will go a long way toward helping you decide how much genetic testing, if any, might be advantageous for you.

Diet: There are many examples of well-studied genes suggesting certain dietary correlations. A variation in a gene called FTO predisposes people to obesity. It is known that those with a particular alteration in the gene APOA2 lose more weight when they reduce saturated fat in their diet compared to people without the variation. And it is known that more than 10% of American women have a variation in the gene MTHFR that can lead to birth defects like spina bifida in their babies unless the pregnant women supplement their intake of folate. With 100 million known DNA variants and many thousands of food chemicals, the body engages on top of our blended make-up, it is easy to see that science has just begun to understand that a diet based on genes is far more complex than it once seemed. You can safely give all those “eat for your genes” books and blogs a pass for now.

Disease: At present, about 2000 diseases can be identified through genetic testing. In some cases, this allows for better management of conditions before they become symptomatic. For women carrying one of the BRCA genes for breast cancer, lifesaving measures may be taken to virtually eliminate risk of the deadly form of the disease those with the genes carry.

However, as with diet, the picture is not always so clear, and the consumer-oriented DNA testing companies have had to change their policies with regard to what they reveal to their customers. (Originally, consumers had to choose to “unlock” certain sensitive information because of how upsetting it could be. Between 2013 and 2017 the consumer testing companies were not allowed to reveal potentially upsetting genetic information, but as more and more consumers have been hiring third-party labs to analyze results, those restrictions have been relaxed somewhat.)

In most cases, as with diet, there is simply not enough data to reliably predict what variants or unstudied combinations of variants in your DNA will do. So the question is begged: How much do you really want to know since there is no way to know it all? Clearly, you would most likely want to know about the BRCA genes. But what if you found out you were 100% destined to get Huntington’s, a devastating brain disease that destroys nerve cells. Maybe you would, maybe you wouldn’t.

The science is getting better all the time. More data will clarify choices for some people on the fence about which information can help and which would only contribute stress and uncertainty.

To know or not to know

Until then, strategies for being comfortable with “not knowing” may help not only with how we cope with our own health issues but also with how we digest and learn to live with the many unknowns of the coronavirus pandemic the entire planet currently finds itself mired in. So many debates about the virus itself, as well as the disease it causes and the myriad ways different countries have responded, have exposed our cultural insecurities around “not knowing”.

“Not knowing” is the ability to accept what is, free from pre-conception or bias based on fear or ignorant presumption.

The human brain is wired to fill in the blanks when it can’t quite make out the whole picture. As a survival mechanism that means we see a snake when a few inches of an old piece of coiled rope show through a pile of fallen leaves. While useful in that context, we have lamentably witnessed and are still in the grip of the terrible dangers of jumping to snaky conclusions by thinking that today’s headlines provide knowledge about the never before seen disease that has brought humanity to its knees and been studied for barely half a year. Polio was first identified in 1789. The vaccine came in 1954.

In some spiritual contexts, “not knowing” is a position of strength rather than weakness. It is the ability to accept what is, free from pre-conception or bias based on fear or ignorant presumption. This ultimate innocence, not at all naiveté, leaves us wide open to research-based knowledge, ever changeable as new data emerges, and can be very liberating to the human spirit, unifying to us all collectively. We are all in this together, after all.

Once all 3 billion pairs of DNA have been thoroughly studied, we might be able to dispense with the life skill of “not knowing” about the direction our health may take, but until then, fitting into our genes may require some being at peace with the mysteries of life.

Ann Constantino, submitted on behalf of the SoHum Health’s Outreach department.

Related: Colds & Flu, Lab, News, SoHum Health, Wellness