Teenage Mutant Coronavirus

By Galen Lastko,

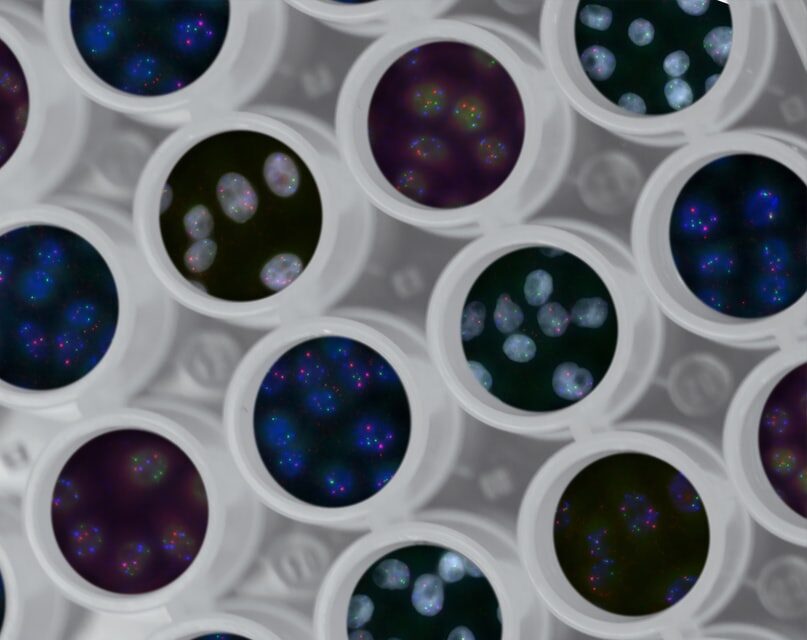

Photo by National Cancer Institute on Unsplash

Published in the Humboldt Independent on August 18, 2020

Ever since the inaugural Coronavirus season kicked off this year, there’s been all kinds of whispers about what might happen if the virus mutates. There’s always a chance that anytime DNA or RNA is replicated (for example, during cellular mitosis or when a virus makes copies of itself using a host cell), things might not get copied 100% correctly, resulting in changes to the organism or virus commonly referred to as “mutations”. In theory, a mutated form of COVID-19 could force us to change our strategies for combating the virus.

As tiny as viruses are, they contain a wealth of genetic information in their RNA, just like pretty much every other kind of critter on the planet.

I was understandably a little surprised to learn that almost 4,000 COVID-19 mutations have already been tracked, according to the Howard Hughes Medical Institute’s study. And while it’s important to track these mutations, as they provide insight into how the virus functions as a whole, the vast majority of them have no impact on how the virus behaves, at least, not as far as humans are concerned. As tiny as viruses are, they contain a wealth of genetic information in their RNA, just like pretty much every other kind of critter on the planet, and to the best of our knowledge, only certain parts of the viral “code” could mutate in ways that would in turn impact how we are able to handle the disease. Most viral mutations simply do not affect the viruses’ interactions with human immune systems.

Lest we fully shed our paranoia: the most concerning of these potential mutations might occur in the viruses’ “spike protein”, which is designed to bond with a protein on human cells called ACE2. A more effective spike protein could (again, in theory) arise as the result of mutation, which in turn would increase the rate of successful cellular infections. While such mutations are possible, there are no clear indications so far that different “strains” (varieties of the virus distinguished by commonly shared mutations) of COVID-19 will present different challenges to the medical community, but it is certainly not beyond the realm of possibility. It is also a small comfort that COVID-19 is less prone to mutations than other RNA viruses such as HIV or influenza, which further reduces the possibility of widely disparate strains of COVID emerging.

Influenza manages to switch itself around enough each annum to warrant a new batch of tailor-made vaccines and immune responses.

Last week, a cooperative study conducted in Venezuela by the University of Glasgow, New York’s Mt. Sinai Hospital, and the Incubadora Venezolana and Universidad del Rosario identified an allegedly “much more aggressive [strain of the] virus” after analyzing local samples of COVID-19. Specifically, they discovered “a point mutation in the Spike protein gene, previously reported to be associated with increased infectivity, in all three Venezuelan genomes.” The researchers complained that the Venezuelan government’s exclusive control of COVID-19 information, resources, and genetic information impeded their process, saying that “this is a time for open science.” And in a world less beholden to political ineptitude, we might have a better shot at just that.

Of course, as long as we’re dreaming, I’d like a pony.

The fortunate reality is, different strains or mutations of COVID-19 have not been shown to impede the process of generating antibodies or otherwise responding to the infection. Influenza, comparatively, manages to switch itself around enough each annum to warrant a new batch of tailor-made vaccines and immune responses. So whether the latest rumors of a Russian COVID-19 vaccine are legit or not, or whether we’re still a ways away from any kind of viral endgame, there’s no reason to believe that we’re one mutation away from a super plague: COVID-19 is just a little too fastidious and set in its ways to get that creative on us.

At least, so far.

Galen Lastko, submitted on behalf of the SoHum Health’s Outreach department.

Related: Colds & Flu, News, SoHum Health